Regional Arts WA Artist of the Month – Tina Carmody-Elliott

When I call Tina Carmody-Elliott, she’s making coffee. There’s the distant sound of a kettle, the clink of a spoon, and then she’s there – warm, direct, ready to talk.

“It was awesome,” she says, when I ask about growing up in a household where art was part of her DNA. Her father was a brilliant guitarist who’d have jam nights at friends’ houses, and young Tina would tag along and join in. By nine, she was learning the violin. Her mother used paint to interpret the bush and Country. And Tina was the kid who had to draw on everything, big murals sprawling across her bedroom walls. “I was lucky to have parents that actually let me paint on the walls,” she says.

Today, that childhood freedom has crystallised into something formidable. Tina describes herself with a phrase that’s become her signature; “I was born with a treble clef in one hand and a paintbrush in my other.” She’s a classically trained musician who plays piano and violin, an award-winning visual artist who’s won the City of Kalgoorlie-Boulder Art Prize twice, and someone who’s exhibited at the John Curtin Gallery multiple times. But labels don’t quite capture her. Tina’s also working in wood burning, resin, pyrography, VR documentaries, and hand-painted pens.

“I like to challenge myself and try different things,” she tells me. “I don’t want to become an artist that sticks to one thing. It just becomes routine.”

That restlessness has led her from painting 1.5-tonne tree trunk sculptures for public spaces to decorating tiny pen barrels for a collaboration with Dr Sean George, a project they called “Tjunguringkula Waakaripai,” which means ‘working together’. As we speak the pens have become so popular they’ll soon be heading to Federal Parliament as gifts for dignitaries.

Country and Connection

Tina is Anangu, Spinifex (Great Victorian Desert) and a traditional owner for Upurli Upurli Nguratja (Cundelee) and Kepa Kurl (Esperance). Her mother’s people are coastal, the Wudjari people, from the Esperance area, with her grandmother’s Country stretching from Thomas River across to Cape Arid. Her father’s side is Spinifex, from the Desert. Born in Esperance, she grew up in Kalgoorlie, and when she speaks about Country, there’s a physicality to it.

“You just get this need sometimes to go put your feet in that ocean and just breathe that air,” she says. From her home base in Kalgoorlie, she and fellow artist Debbie Carmody will make the drive down to Wudjari whenever the warmth returns. “It seems to be inbuilt in us.”

Her designs draw inspiration from childhood lessons, trips out bush with family, gathering tjala (honey ants), maku (bardi grubs), and mai (bush vegetables, fruits, and seeds).

When I ask about the Seven Sisters story that has come through in her past work, Tina is careful. “I don’t talk about the Seven Sisters story because it’s a special story. You need to get that story from those people.” Then she offers a generous thread, “They were strong, strong black women. As they travelled and stopped and rested, they created the waters and life on the land. That’s the bit that I use in my artwork. Everything originated from strong black women.”

The Work

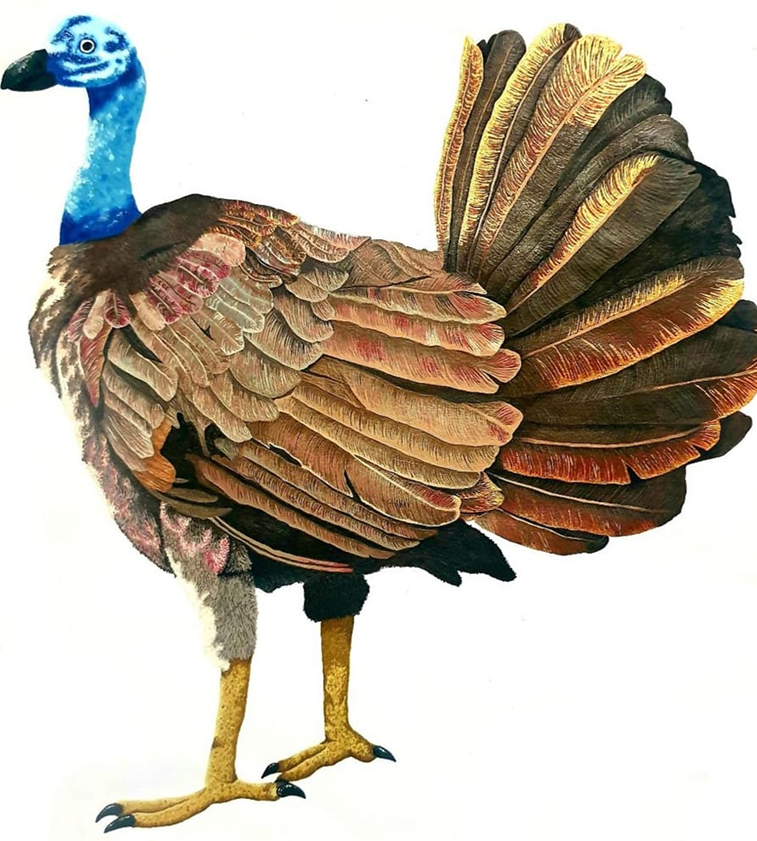

Recently, Tina painted images of megafauna for the Tjuma Pulka Nullarbor Plain Mega Fauna Project, including extinct creatures like the Progura, rendered in what she calls her ‘fine art style’ with up to ten layers of glazing. “The photograph doesn’t really do it justice,” she says. “You need to actually see the artwork itself to actually really get all the fine details.” Later, these images will become part of a VR documentary and animated digital projection.

She’s currently working on the primary artwork for Community Arts Network WA (CANWA)’s Legacy Project for the Goldfields region, painting “lots of little birdies,” she describes with a chuckle. The birds will be photographed throughout the process and potentially published in a book.

With all projects, Tina sees them as challenges and doesn’t fear asking for help. Working with fellow artists Debbie Carmody and Monika Dvorakova on the Kalgoorlie City First Nations Public Art project, they tackled the massive tree trunk sculptures, the Ngurra Walkurta poles now standing in St Barbara Square, working alongside engineers who’d never done anything like it before.

“It was a massive challenge and learning curve for me,” she says. “To the point where sometimes I actually thought I’m not gonna be able to do this. But I persevered and got through it, and now they’re just wonderful.”

The collaboration extended even to the technical side. “Even the local engineers in town here, they had never had a project like this as well,” she says, laughing. “They were all scratching their heads. But we were all learning and tackling each hurdle right from the start together.”

The Harder Conversations

Tina doesn’t shy away from the politics embedded in First Nations art. As part of that same public art project, Debbie Carmody’s glass honey ant sculpture, a very popular installation, was deliberately smashed. Despite full surveillance, the council didn’t pursue charges.

“It just raises questions,” Tina says. “Somebody’s destroyed this honey ant, but nothing’s been done.” It’s the absence of saying anything or doing anything that really speaks volumes. She contrasts it with the media storm when someone damaged the statue of Paddy Hannan. “It was all over the media. But this? Nothing.”

At the recent Goldfields Art Prize, where she, Debbie, Brent, and Mia all exhibited, the judges had no First Nations representation or experience with First Nations art.

“It’s really, really important when you are having these competitions that you need to get proper representation,” she tells me. “I always have an Indigenous judge on the judging panel, knowledgeable about art. Because there’s so many of us that have different styles of art, and we can’t be stereotyping artwork. We’re in the year 2025, and we’re still having discussions about what constitutes proper Indigenous art, what is representative. Because it’s not all about dots.”

She’s quick to add that the placement of the judges was not done deliberately and that she has a meeting coming up with staff at the Goldfields Arts Centre to address these issues for future prizes.

She’s not dwelling. Tina is a powerful artist who has already identified national competitions, and earmarked them for herself. “I feel that I’m ready” she says.

As we finish up, I get the sense that as an arts community, we’re watching someone on the cusp of something bigger. The national competitions. The VR documentaries. The pens in Federal Parliament. Tina Carmody-Elliott is an artist who refuses to stand still, who moves between mediums and scales with the same ease she moves between violin and paintbrush, between learning curves and completion, between desert and ocean. Always ready for the next challenge, always willing to collaborate, and always speaking truth.

Watch this space.

Posted in Artist Profile, Our News, Stories.